In this post, I’ll cover some of the work I’ve done on the initial version of the ECS for Iris Engine. Before I get into that, I’ll summarise the other work I’ve done prior to implementing the ECS.

Currently, the engine consists of:

- A way of creating and managing multiple window instances via GLFW

- Logging via spdlog

- A very rough basis for an OpenGL renderer, with function loading via glad

- A generic event bus

- Input management, including the ability to register keybinds with primary (and optionally, secondary) binds

Needless to say, there’s a long way to go. Writing an ECS when there’s still so much to do on some fundamental systems is probably a little premature, but of all the possible next steps to take, it’s the thing that interested me the most.

I should point out that I have no intention of attempting to innovate with my implementation. The ECS architectural pattern has been popular for a very long time and its principles have been talked about as far back as almost twenty years ago, when Scott Bilas detailed some aspects of it in his GDC talk, “A Data-Driven Game Object System”. Many variants and evolutions of it have emerged since, but the core ideas remain the same.

What is an ECS?

If you’re not familiar with it, in brief, it’s a compositional, data-oriented approach to defining game objects and their behaviours. It consists of:

- Entities: unique identifiers for game objects. Sometimes they’re objects with common properties (such as position and scale) defined on them directly, but those are usually handled via components.

- Components: containers for different aspects of an entity’s data, such as physics properties. Component instances are the constituent parts of entities and are usually stored in arrays or maps for easy lookup via entity IDs.

- Systems: where the logic resides. A system is associated with one or more component types and processes entity data by iterating over all of the components matching those types per tick/update/frame and modifying the data in them.

Because it’s so prevalent in modern game engines, it should be no surprise that there’s an abundance of ECS libraries across many languages, with C++ in particular having a number of well-established options such as entt and EntityX. There are also many articles, forum posts, and other materials that discuss ways of implementing the pattern; some are more rough and ready, others go deeper into the topic and accommodate things like enhanced memory efficiency via custom memory allocators.

What I did

For my purposes, I wanted an approach that isn’t too difficult to learn, but also doesn’t compromise too much on efficiency. The approach described by Austin Morlan seemed like a good middle ground, so I used that as a reference.

For the most part, I’ve not strayed far from that approach and largely have the same implementation. In summary:

- Entities are just integers (IDs).

- Component types are structs. When a component type is registered with the

ComponentManager, it’s assigned a numeric ID, similar to entities. This allows component types to be referenced and stored by entities and systems. - Every entity and every system has a

Signature, which leverages std::bitset to specify component types and enable any given system to operate on entities that have the components it’s interested in. EntityManagerdeals with the creation, destruction, and “signing” of entities.ComponentManagerdeals with registration and retrieval of component types, as well as providing a way to add/fetch/remove an entity’s components via theComponentStore.ComponentStoreis instantiated per component type and provides an array of components per entity. It maintains a map of entity ID to component index and another of component index to entity ID for easy lookups from either angle.Systemis an abstract class extended by each distinct system and provides some convenience methods for specifying component types, retrieving components by entity ID, and adding/removing entity IDs that the system should operate on.SystemManagerdeals with the registration and “signing” of systems, as well as adding or removing entity IDs on them whenever an entity is destroyed or its signature is changed.

There are a few parts I handled differently. The biggest difference is the omission of the Coordinator class, which is designed to coordinate the EntityManager, ComponentManager, and SystemManager. I instead opted to implement those as singletons, which is consistent with the *Manager classes I’ve implemented for other parts of the engine; this is something I’ll probably revisit as I’m not especially keen on singletons, but for now, it’s fine.

Something else I did slightly differently is leverage my existing event system to deal with events within the ECS. SystemManager uses it to respond to entities being destroyed or their signatures being changed:

class SystemManager : public EventHandler<DestroyEntityEvent>, public EventHandler<EntitySignatureChangeEvent>{public:

// ...

bool Handle(const DestroyEntityEvent &event) override { for (auto const& [_, system] : m_systems) { system->RemoveEntity(event.GetEntityId()); }

return false; }

bool Handle(const EntitySignatureChangeEvent &event) override { for (auto const& [type, system] : m_systems) { if ((event.GetSignature() & m_signatures[type]) == m_signatures[type]) system->AddEntity(event.GetEntityId()); else system->RemoveEntity(event.GetEntityId()); }

return true; }

// ...

};Sidenote: event handlers return a bool indicating whether or not they consume the event, preventing subsequent handlers from receiving them.

Similarly, ComponentManager notifies components when an entity is destroyed, and EntityManager generates a new signature for an entity when a component is added to or removed from it (which, in turn, dispatches an EntitySignatureChangeEvent, handled by SystemManager as seen above).

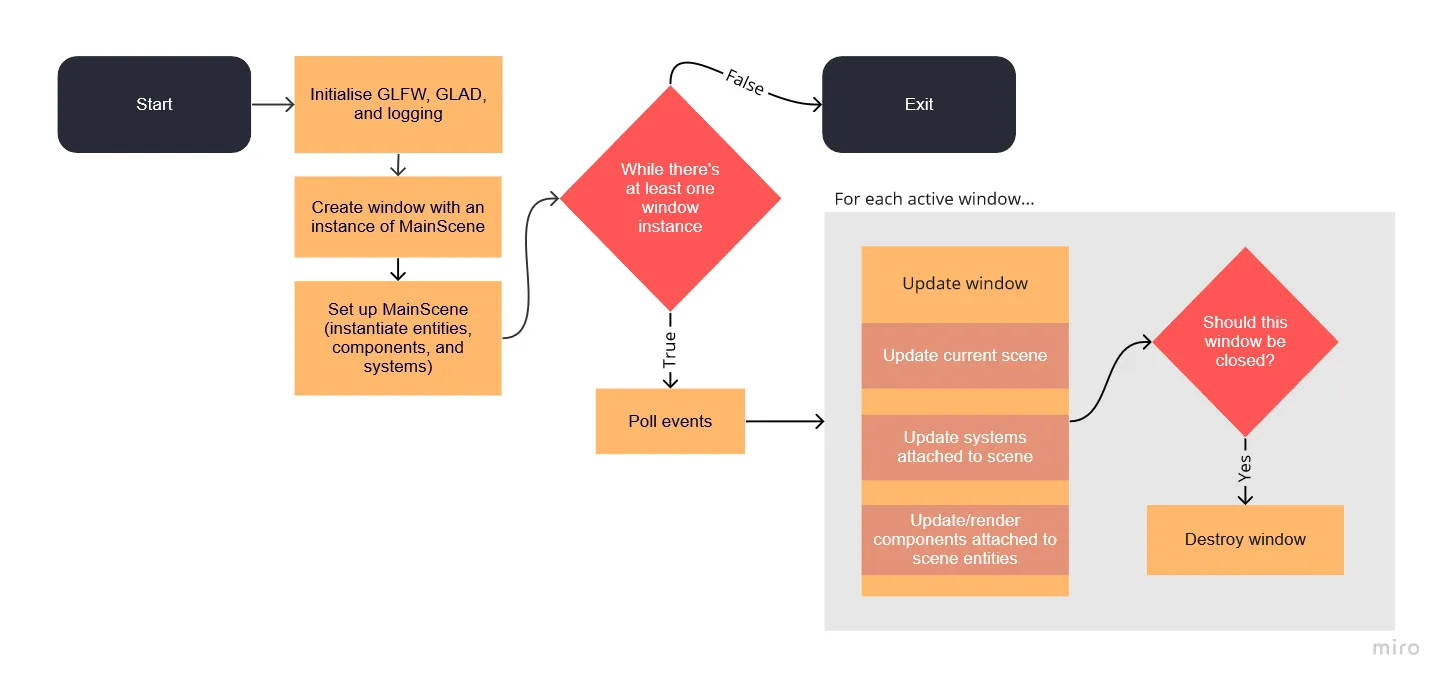

With the ECS factored in, the overall process looks something like this:

Still a bit primitive, but better than it was without the ECS, where I used classic game objects with inheritance.

What’s next

There are lots of ways to go from here; further work on the renderer, implementation of a scene graph, work on formats for storing entities/components on disk and loading them from there, and a ton of other stuff I’m not thinking about yet, like audio, and concurrency and parallelism.

One of the current issues is that scenes are implemented very primitively, where each scene has a concrete implementation that takes care of its own setup, interacting directly with the ECS. For example, MainScene currently looks like this:

class MainScene : public Scene{public: void Setup(float aspectRatio) override; void Update(Window&) override; void Render(Window&) override; void Teardown() override;

private: std::shared_ptr<CameraController> m_cameraController; std::shared_ptr<LightingDemo> m_lightingDemo; std::shared_ptr<MeshRenderer> m_meshRenderer;};Although scenes/levels/worlds aren’t part of the ECS pattern and there are many ways of dealing with them depending on specific requirements, this arrangement is far from ideal because it goes against the data-driven nature of the ECS, so it’s probably the next thing I’ll tackle.